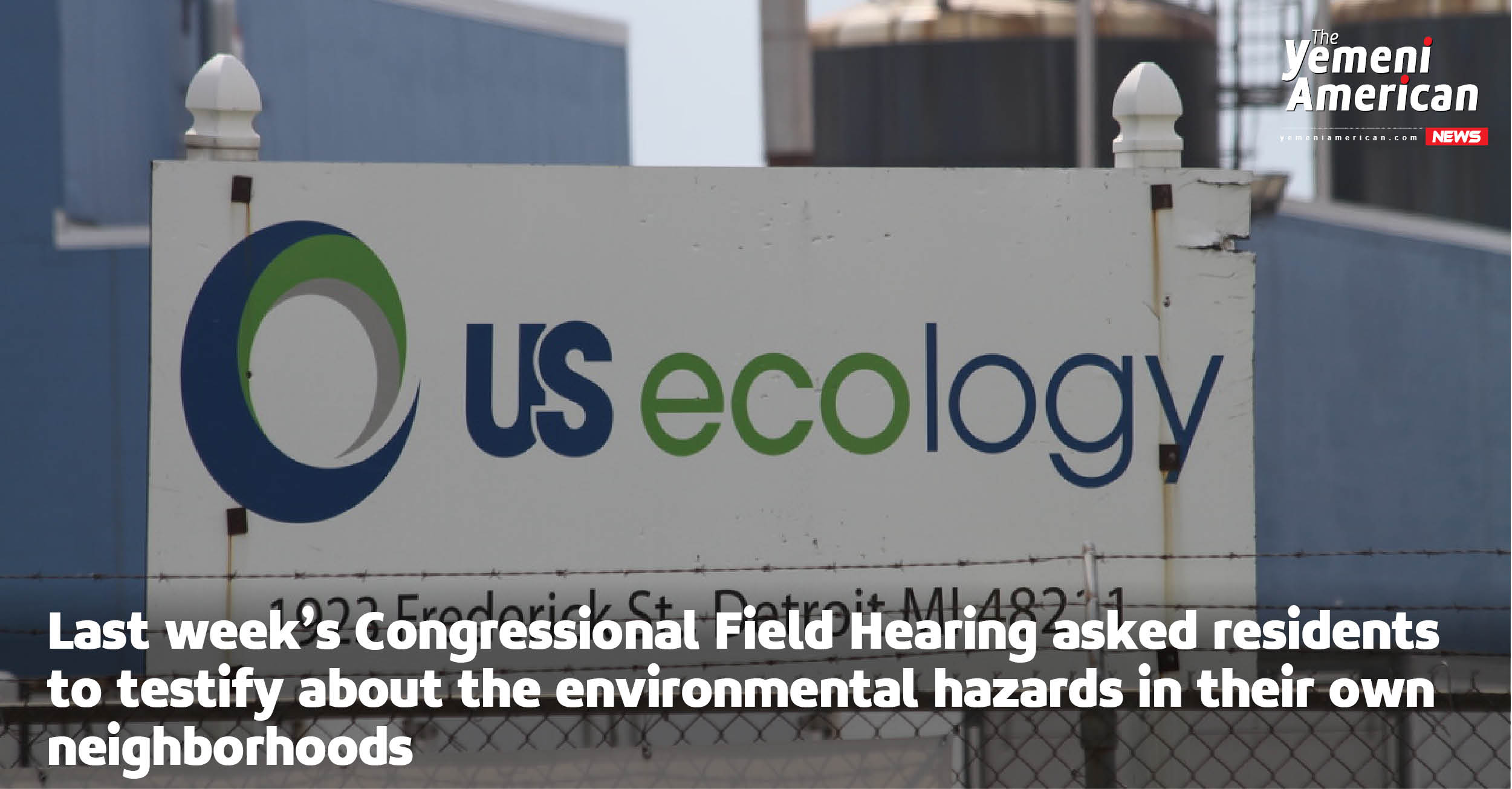

Last week’s Congressional Field Hearing asked residents to testify about the environmental hazards in their own neighborhoods.

By Simon Albaugh – Yemeni American News

Detroit, Mich. – It doesn’t take much to recall the proposed expansion of US Ecology’s Georgia Street facility. After hearing about a 10-fold expansion of the hazardous waste processor’s storage capacity, the Hamtramck and East Side communities came together to fight back against the proposed expansion. But meetings, public hearings and protests didn’t matter in the end. And the neighbors closest to US Ecology now suffer the most.

“The city and state regulatory agencies have done little to address our concerns,” said Pamela McGhee, a Detroit resident who lives near US Ecology. “My neighbor, who lives half a block away from US Ecology, has COPD and Asthma, and can’t go outside. She has to close all her windows and has a breathing machine inside.”

This past Wednesday, Detroit residents impacted by what they say is pollution from the US Ecology and Stellantis facilities in Detroit’s East Side were asked to provide testimony to the United States House Oversight and Reform Committee. The field hearing, which happened at Wayne County Community College, was run by Representative Ro Khanna (D-CA), chairman of the subcommittee on the environment, along with the subcommittee’s vice-chair, Representative Rashida Tlaib. Representative Debbie Dingell also was there to ask questions of the residents.

The field hearing on effective environmental enforcement asked residents of Detroit and experts in environmental justice to weigh in on the current legal landscape for potentially harmful environmental factors in the harshest environments of the city. Areas where heavy industry, like hazardous waste processing or automotive manufacturing, are disproportionately impacted with the harmful effects of pollution from that industrial activity.

In McGhee’s testimony, she talked about the smells of the air pollution that has come from her neighborhood. On Detroit’s east side, where Detroit Renewable Energy ran a garbage incinerator that was shuttered in 2019, communities are still reckoning with the impact of a lifetime of pollution.

“The lack of regulations to [the incinerator] caused a lifetime of respiratory and cardiovascular issues to my community that still lives with them,” McGhee said. “COVID hit us hard because the EPA did not do its job regulating incinerators like these, causing us to breath in small particles of trash. If the EPA were to regulate incinerators 16 years ago, we would not have lost so many of our neighbors.”

McGhee’s daughter, Daeya Redding, echoed this sentiment, saying “it was this pollution that made our community susceptible to COVID-19. Community members already suffering from asthma and respiratory illnesses were hit the hardest.”

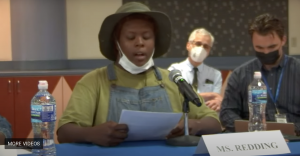

Daeya Redding provides testimony to the House Oversight and Reform Committee’s Subcommittee on the environment (Source: House Oversight and Reform Committee Livestream)

Daeya Redding provides testimony to the House Oversight and Reform Committee’s Subcommittee on the environment (Source: House Oversight and Reform Committee Livestream)

Jamesa Johnson Greer, executive director for the Michigan Environmental Justice Coalition, talked about the process of changemaking in her expert testimony. In her expert view, she sees the health disparity from exposure to toxic pollution as an echo of the common racial segregation practice known as redlining. People who own property that’s value is forever impacted by redlining are not as easily able to relocate to environmentally safer, and oftentimes wealthier, communities.

“Hearing the voices of impacted communities and those who work alongside them is critical to the policy changes we need to dismantle the deep inequality that exists in current laws and regulations,” Greer said. “This starts with understanding the discriminatory practice of redlining and the root causes of environmental injustice.”

Executive director of the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center Nicholas Leonard is no stranger to making a case. In 2020, Leonard and the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center submitted a civil rights complaint to the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy (EGLE).

Leonard’s expert testimony focused on the legal framework that has contributed to communities not being able to adequately advocate for themselves. In many cases, administrative departments are told to ignore the unpopularity of a facility, or to not consider the racial makeup of the community where the facility is being located. These and other blind spots, Leonard alleged, amount to outright ignoring black and brown community efforts in any consideration.

“Because the concerns of communities of color are not reflected in the law and required to be addressed, our agencies that make the decisions regarding whether to allow the facilities to be built or expanded must, in accordance with the law, ignore the concerns of people of color,” Leonard said. “Put another way, the law ignores people of color, and as a result the agencies in charge of administering these laws do as well.”

All of this has lead to a situation in which 65% of Michigan’s minority populations are located in what’s been determined as environmental justice hotspots, places where health risks are worsened and exposure to toxic pollution isn’t a rarity.

Communities know what’s happening to them. And in front of Congressmembers and dozens of media outlets, they made their demands for change.

“We want all facilities to stop operations if they cannot fix their pollution issues,” Redding said. “As we are paying for their pollution with our lives, our children’s lives, our bodies, and our futures, EGLE and the EPA are not doing enough to regulate their operations.”